"Everything you like was created by a queer person," musician and DJ Aluna proclaimed near the end of "The Power In Pride: A Conversation Honoring The Resilience Of Black Queer Creatives." (A seemingly bold statement — until you do some digging.)

Ditto a Black person. As the Recording Academy's VP of DEI, Ryan Butler, pointed out, just about every American music genre flows back to that source. "There is no pop music in America that is not a derivative of the Negro spiritual," he said across from Aluna.

"The queerness has been the innovation in it, but the Black community has been the foundation of it," Butler concluded. "So, I think when you have the foundation and the innovation together, it's worth celebrating 365 days a year."

When considering those two truths, two more truths emerge. First, without the contributions of Black and queer people, our world — including our musical landscape — would be unrecognizable. Second, to celebrate only in February, for Black History Month — or June, for Pride Month and Black Music Month — would be a grave disservice to both wellsprings of genius. Honoring Black and queer creators, as Butler pointed out, requires the entire calendar year.

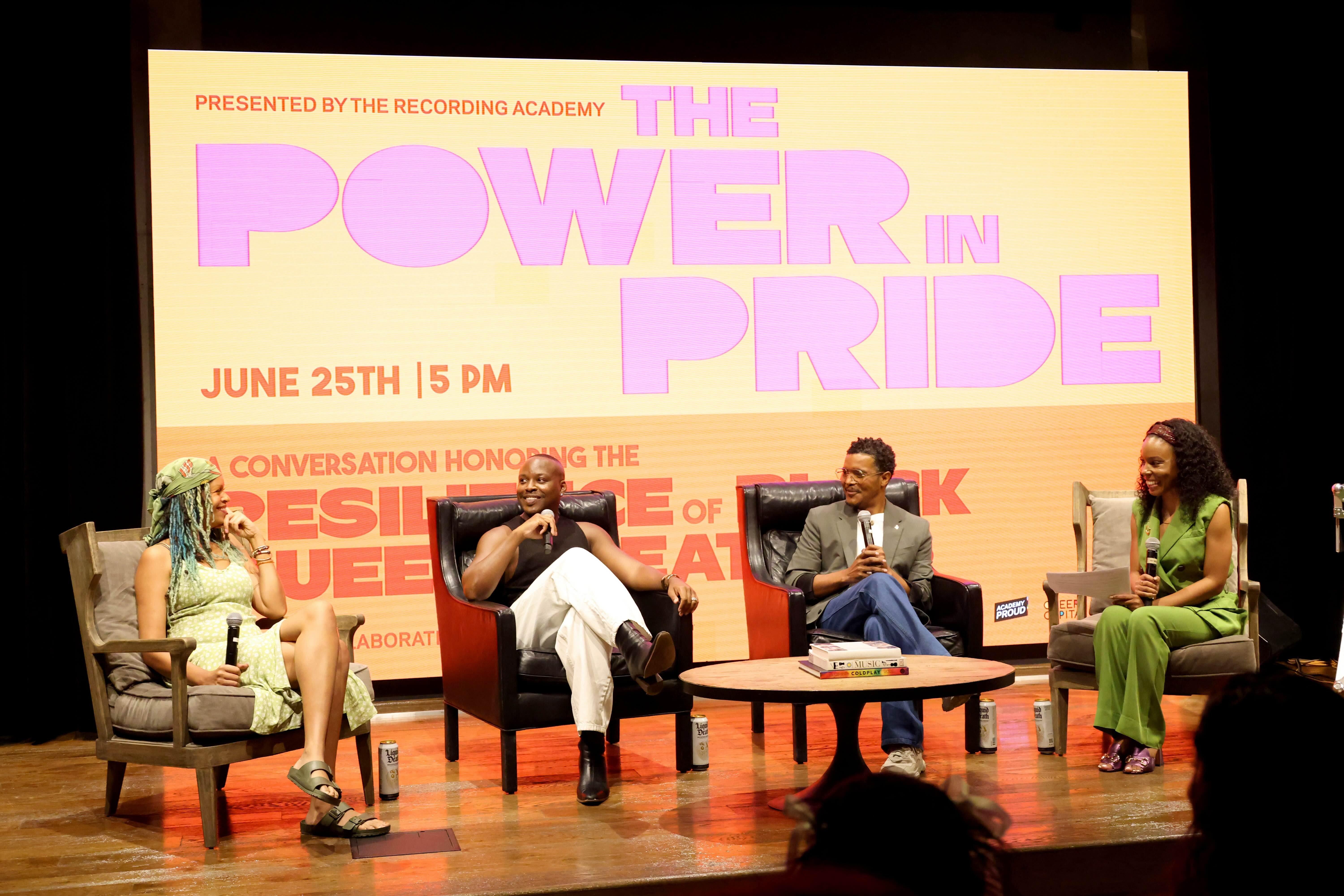

These themes were paramount at "The Power of Pride," a candid conversation at the Live Nation building in Manhattan, just as summer kicked off. Tiffany Briggs Low, the Director of Corporate and Communications at Live Nation, moderated the discussion between Butler, Aluna, and third panelist Bryant K. Von Woodson II, VIP Relations at Chapter 2 Agency and Head of Communications at Queer Capita. Von Woodson II introduced himself as a "curator of people" who connects BIPOC folks with crucial opportunities; Butler, as an "angelic disruptor"; Briggs-Low called Aluna "our sister in green" and "the curator of the vibes."

Briggs-Low kicked off the conversation with a heavy, dual prompt: "I would love to hear about why you feel it's important for the world to continue celebrating both Pride and Black Music Month, and what does the intersectionality of Black and queer identities mean to each of you?"

"I think that theme months each year do serve as a reset," Aluna stated, "and have you looking internally, and looking at what you've done and haven't done, and how you feel. To me, the queer community and the Black community have given so much," she continued, "and my mission is for us to just turn that around — to be giving it back to ourselves. Because there is an abundance of things that we create — and we never stop creating — but we need to be fed, and the well is running dry. And that upsets me."

To Aluna — who is Black, straight, and an ally of the Black queer community — this nourishment comes from "creat[ing] space" within these communities, and fostering "spirituality and deep, deep connection."

To that question, Von Woodson II — who is Black and queer — paraphrased Maya Angelou: "Between both communities, I stand as one, but I also really acknowledge the 10,000," he said referring to the philosophy from Angelou's work that credits the collective experiences of communities and ancestors who came before.

"I think that's what this month is about," he continued. "Celebrating the 10,000 that got me to be able to sit on this stage, to have this conversation with you, to sit up here with some beautiful Black people, and really speak about our lives and ourselves."

Butler, who is also Black and queer, calls that intersection "a superpower." Yet the world doesn't always treat it as such — to put it lightly. As Butler related, just last weekend, he entered a function in Malibu, where the host said, "I'm going to sit you at the table where all the rappers like to sit."

"I don't really give rapper," Butler mused dryly. "You shouldn't be profiled in that type of way, and I definitely experience it in the corporate environment, still. I don't think that it always feels like a safe space.

"But that's also a litmus test for me," he added. "I know that there are other [people] who may feel this way, and so it also helps me make sure that I'm constantly applying pressure."

Von Woodson II expounded on the importance of being his authentic self, in spaces that might stifle that. "There is no hiding that I am clearly Black, but also queer," he said, before showing off his proudly flamboyant style of walking into a room.

"As I work with my clients, and I work with new people, I think I show up as authentic as I can," he continued. "And I just lay it on them and say, 'You either take it or you don't.'"

Aluna, for her part, highlighted the unfairness of Black artists being pigeonholed as featured artists.

"If I need to be an example of what's possible for the next generation, they can't just see me as Disclosure featuring Aluna, DJ Snake featuring Aluna, Avicii featuring Aluna, because that gives the message that that's all we're worth," she said. "You can't get booked as an artist in your own right, because they just don't see you as an artist.

"Managers across the board, bookers, labels — they're just hankering after your essence, your soul," Aluna continued. "But without your Blackness."

In supporting Black and queer communities — which takes a plethora of forms, for all different kinds of people — Butler warned against performative gestures. Aluna decried "the colonial separation between Blackness and queerness."

And Butler left the audience with a truth bomb: "There are going to be times where you are going to have to shield me with your privilege that I don't have."

But for all these heavier-than-heavy topics of identity, justice and belonging, "The Power In Pride" felt celebratory and familial. As the conversation wound down, the beats were turned up, and the audience was geared to get out and uphold Black and queer genius and solidarity — 365 days a year.

The Recording Academy thanks its partners — Live Nation and Queer Capita — for their efforts to make this event possible.